You are currently browsing the monthly archive for December 2013.

On the last day of 2010, I created a list of my Top Ten Blog Posts up until that time. Three years later, I think it’s time to do it again. So, here are my favorite blog posts of the past three years.

(Note: this list doesn’t include the excerpts from my book that I’ve posted. For those, go to the book’s Table of Contents. It also doesn’t include the Chapter Companions for my book, which have photos and extra stories to go with each chapter.)

TOP TEN POSTS

- Wedding Bells (June 2013)

Pretty much the most exciting thing to happen to me in the past three years was getting married. Here are some of my favorite pics from the celebration. Minus the tornado sirens going off the night before… - Book Tour Report (May 2013)

The other most exciting thing was touring with my book — I did nearly 100 events in about 20 states and 3 Canadian provinces. Here’s the report back from the first leg of the tour. Good winds are blowing… - Olives in Salem (Written Fall 2007, posted March 2011)

Harvesting olives in a village near Nablus. - Olives and Movie Stars (Written Fall 2007, posted December 2013)

More olive harvesting (in Battir), a hilarious film shoot at Snobar, and other good times in Palestine. - Statehood bid? What statehood bid? (September 2011)

I visited Palestine in the fall of 2011 to visit friends, do a book tour, and see what the atmosphere was like as Palestinian representatives asked the United Nations to accept them as a member state. Here is what I found. - Grampa Red (February 2012)

My grandfather passed away in January 2012. This is my tribute to the great man — a world-class wood-carver (self-taught in his 60s), amateur fiddler (self-taught in his 80s), cattle rancher, electrician, plumber, carpenter, post hole digger, fence mender, serial cow dog owner, hay baler, tractor cusser, coffee drinker, biscuits-and-gravy eater, and many other things to many people in his long life. - Turks & Caicos & Irene (September 2011)

What do you get when you cross a weekend vacation with a hurricane — twice? Not to mention the little adventure with the kayak… - Galapagos Part 1 (October 2010)

Someone showed me a deal for a $500 ticket to the Enchanted Islands. How could I resist? - Galapagos Part 2 (November 2010)

Islands and boobies, iguanas and volcanoes, beaches and sharks… - Jon Stewart’s Triple Threat (March 2012)

Some daring brilliance by the team at the Daily Show about the Israel/Palestine situation

.

PREVIOUS TOP TEN

.

OTHER RECENT FAVORITES

- Rawan Yaghi — Gaza’s Searing Voice (March 2012)

A young woman with incredible writing skills and passion. One to watch. - Sinai to Canaan (September 2011)

More about my 2011 trip to Palestine. - Life on the Road (November 2011)

Another short piece about my 2011 trip to Palestine. - Poetry (January 2012)

Just sharing a couple of poems I wrote to kick off the new year in 2012. - Turkish Exile (September 2012)

Due to a visa snafu (thanks, US Consulate in Istanbul), my boyfriend at the time (soon to be fiance/husband) got stuck in Turkey for several months. So I joined him there. A few days after I arrived, he proposed! - On (Not) Bending the Arc of History (August 2011)

An article by Drew Westen in the New York Times that eloquently explains why Obama’s presidency has been such a bitter disappointment to people like me who actually (perhaps foolishly) believed he would try to change things for the better in our nation. - Letter to President Obama (August 2011)

I sent this letter and a copy of my book to President Obama, for what it’s worth… - Occupation as a Dead Mammoth (July 2011)

An aptly vile metaphor. - “A Gaza Diary” by Chris Hedges (October 2001)

An almost unbelievable article by a former Middle East bureau chief for the New York Times about the Gaza Strip during the early part of the second Intifada. - On ‘Cycles of Violence’ (March 2011)

Why these cycles are easy to start and a research paper that examines who usually breaks periods of calm between Israelis and Palestinians (hint: it’s not the Palestinians)

Here’s something I wrote when I was in Palestine in 2007. Just hadn’t posted it yet. Some snapshots of life in beautiful Palestine. Good times.

Olives in Battir

On Friday, October 26, I accompanied a friend to Battir village, which is one of the most picturesque villages in Palestine (and that’s really saying something). It’s built on a hillside not far from Bethlehem, and some of its buildings are carved in part from the living rock of the mountain.

Here are a few pictures that can’t really capture the beauty of the village but at least they give some indication. (More pics here.)

The village is surrounded by national park land — the hilly land of four nearby Palestinian villages that Israel destroyed in 1948 and then forested with conifers in order to hide the evidence. You can still find the ruins of these villages if you know where to look. The residents of the villages are mostly living in Dheisheh and Aida refugee camps near Bethlehem now, and they still maintain their identities and their ties with Battir.

A spring runs down from the center of town into the narrow valley below, where it’s caught in a reservoir at night and apportioned to farmers during the day according to ancient custom.

Battir has a unique relationship with Israel because the village is right on the Green Line, and much of Battir’s land is on the Israeli side of the Green Line. Israel wanted control of a Jerusalem-to-Tel Aviv railroad line that follows the Green Line as it passes through the middle of Battir’s land.

The deal they worked out seems almost inconceivable today: Israel agreed to allow Battiris to access their land on both sides of the Green Line if the village would allow Israel to control the track through it. (Later the Israeli government tried to build the Wall through Battir’s land, which would destroy much of it and most likely cause the collapse of their ancient farming techniques. here’s a recent article in Haaretz about how its unique and historic ecology is threatened by the Wall.)

We caravanned out to some land on the other side of a hill to harvest with two older Battiris and their two grown daughters, both of whom live and work in Ramallah. Another American girl with us, who works with a Palestinian Ministry, and we chatted about fascinating issues in international law, development, Ministry planning, and scholarships for various international graduate schools while we climbed around the dusty trees. They also mentioned they have a neighbor in town who looks exactly like George Clooney.

The daughters told us Battir was known in the area as a relatively progressive village, and Battiris sort of looked down their noses at the other villages for being less educated and more closed-minded.

Of course, I said, the surrounding villages probably looked down on Battiris for being more likely to go to hell. Just like Methodists and Baptists in my home town of Stigler. Everybody’s gotta have some reason to feel better than other people.

Battir’s call to prayer was prettier than the one from the nearest village, though. Battir definitely gets a point for that.

A carload of Swedes joined us eventually (they were in Palestine working on some sort of student radio journalism project), just in time to sit down to a massive picnic lunch of home-made maqloubeh and farmer’s salad.

After another half an hour of work the olives were done, and we headed back into town to wash our hands in the spring and munch on grapes, home-made fruit-roll-up-like things made with grapes and sesame seeds, and coffee on yet another porch looking out on yet another breathtaking panorama.

Porches with great views seem to be one of Palestine’s most abundant natural resources. If one could put a price on and export such things, I have no doubt Palestine would be rich as the Emirates.

Film Shoot in the Pines

Back in Ramallah the next day, there was a film shoot at Snobar (an outdoor cafe and public pool nestled in pine trees on a hillside, hence the name, which means “pine”). The film is being made jointly by various Europeans, Palestinians from Israel, and Palestinians from the West Bank, and mostly with Palestinian money, which I was told was a first.

I arrived on time (which translates into Arab time as “two hours early”) in order to play an extra during a wedding scene. I chatted with the Palestinian boom operator from Nazareth and the German sound man while I waited for the shoot to begin.

Snobar was done up beautifully with lights in the overhanging vines and trees and on the bushes, little bowls with flames scattered around, centerpieces of local green grapes, pomegranates, and fuchshia flowers on white tablecloths, stone steps for the wedding procession, and tall lighted delicate silver wire cylinders.

My friend Muzna showed up with her French boyfriend, and we were joined at our table by the wife of the “actor” who was playing the Best Man — actually the owner of the Zeit ou Zaatar restaurant on Main Street in Ramallah (which was also doing the catering for the shoot), who walked around in his tux and red bowtie and slick hair and make-up like he’d been doing it all his life. He jokingly offered us autographs for five shekels each.

Three other men joined our table and we talked and joked in a mix of Arabic and English and French. We were having so much fun we didn’t mind too much when there was another delay that left us sitting there for an extra half hour. I suggested we merely pretend we were hanging out at Snobar, and a couple of us even managed to finagle a beer out of the owner, even though you’re not really supposed to have alcohol on a film set. (Any time you say “supposed to” in Palestine, it’s generally taken as a challenge.)

The technicians worked around us setting up the camera track and the lighting as the sun set and the moon rose. The lighting made it seem like broad daylight on set all night.

Finally the actors playing the bride and groom showed up. The bride was a slim, radiant, curly-haired half-Egyptian half-Palestinian who grew up in Lebanon, and the groom was an impossibly handsome Palestinian who looked like Cary Grant dressed up as James Bond.

The wife of the “Best Man” at our table, eyebrows raised, said what we were all thinking:

“Al Arees ktir zaki, ah?”

It’s difficult to translate this well. Al arees means the groom. Ktir means very. Zaki means delicious or tasty or savory, but in kind of a delightfully unctuous way. And Ah is slang for yes. So you can say, “The groom is quite tasty, yes?” But it sounds infinitely better in patrician, matter-of-fact Arabic.

The bride was a delight, too. Even between takes she would dance around and flirt with everyone. Half a dozen men from Nazareth came dressed up in baggy pants, black shoes, gold cummerbunds, maroon shirts and gold vests to provide the drumming and singing for the wedding party.

The trouble was, once they got started drumming and singing, it was hard to get them to stop. They’d get into the music like it was the real thing and not even hear the director when he yelled, “Cut!”

At the end of the wedding scene, when all the guests were supposed to go out onto the floor and dance to a Nancy Ajram song along with the bride and groom, the DJ would let everyone dance and clap long after the director yelled “Cut!” He almost seemed to forget it wasn’t a wedding; as if it would be rude to cut the music off while everyone was having such a good time.

Then they’d have a scene of guests at the wedding talking, and some of the guests would wander off while the cameras were rolling in order to talk to a (real, not pretend) friend at the next table. When the sound guy would ask a table to just give him twenty seconds of straight clapping, it was utterly beyond them. Within five seconds of starting to clap, they’d be adding counter-rhytms, singing, and shouts. Sometimes the drummer would start up, too, unbidden. It was like herding ducks.

But it was genuine. If they were going for verisimilitude, they had it.

I wondered if people on most film shoots had this much fun.

The Best Man threatened to steal the show, though, because his personality was so singular and unabashed. He was a terrific actor, playing his part with effortless commitment. He seemed so generally ebullient and talented that he would probably excel at just about anything he tried. Indeed, he owns one of the zakiest restaurants in town. His wife told us he gets up sometimes late at night and cooks feasts for her. She said he loves doing it.

He came by our table after the shoot was finished, when we were finally served our free dinner from Zeit ou Zaatar, which was our only pay. He had a single large clove of roasted garlic in his hand, which he squeezed out onto his wife’s plate, scooped up with some of his restaurant’s bread, and fed to her. Then he skipped away singing cheerfully in Arabic, “No kissing tonight!”

Lucky woman.

It was all good fun. I can’t wait to see how it comes out on film.

Afterwards I was all dressed up with no place to go, so I headed to Zan bar in my formal make-up and black dress to see who I might run into. Sure enough I ran into six people I knew (and this was on a slow night), one of them a Palestinian from Qalandia who speaks almost accentless English and looks European. He welcomed me back to town (this was the first he’d seen me since I came back to Ramallah) and asked what I was up to and why I had come back. I said, “I don’t know, it just feels home-like somehow. I couldn’t stay away.”

He asked me why I thought that was.

I answer this question in a different way each time, and this time the answer I came up with was, “Because the place has a nice culture, a very welcoming culture, that I’m not really a part of, but that I’m always welcome in. So it doesn’t impose on me in any way. I can go off and be whatever I want to be and do whatever I want, and nobody bothers me. But it’s always there waiting if I need it.”

He nodded, lost in thought for a moment. Then he half-smiled and said, “You know, you’re making me fall in love with Palestine even more.”

Bach in Ramallah

Tuesday night, October 30, there was a concert by musicians from the Kamandjati music school here in Ramallah, three Italians and two Palestinians playing concertos and string quartets by Bach, Brahms, and Ravel in memory of Edward Said.

Bach is a favorite of mine, and they played him soaringly. At one point the next song on the program was supposed to be another Bach, but within three notes I could tell it definitely wasn’t Bach. (Which is strange if you think about it. How can a person’s entire style be differentiated based on three notes? Sounds vaguely holographic.) Then I remembered they’d been talking about Ravel, and I figured there must have been a change.

So I was listening to this Ravel piece, and it sounded sad, like a requiem. For some reason I imagined the earth being destroyed and this page of music by Ravel being the only thing left, floating in space.

I wondered if any alien species who found it would be able to (1) figure out that it was a kind of meaningful language, (2) discern that it was a map of frequencies for periods of time, (3) imagine which frequencies to choose, which scale, and which medium — vibrations in gaseous air with a certain density and composition — to bring the original meaning back out, (4) imagine a wooden instrument with metal strings and a rosined horsehair bow that would produce the correct frequencies and sounds, and then (5) extract the complex wealth of emotions and meaning humans feel when they hear the song played.

It seemed hopelessly unlikely.

So I thought of it as a “Requiem for Itself.” And it made me feel deeply sad. But in a satisfying kind of way. Because the earth is still here, after all, in its own devastatingly singular way.

Another Voice

The next night there was another concert at the Orthodox Club featuring several Palestinian artists. It was a counter-concert to the recently-cancelled One Voice concert, which had had a platform for “peace” that participants were supposed to sign on to, but that was discovered to be deeply problematic by discerning Palestinians. Younger students from Kamandjati played first, followed by lute players and singers and Dabka dancers, and finally DAM, a kick-ass Palestinian-Israeli hip hop group.

But before the music started, as is unfortunately customary around here, several dignitaries had to get up and speak and remind everyone that people are in prison and houses are being destroyed and land is being stolen and Palestine isn’t free and we have to be steadfast, etc. Which is fine. But they really do tend to go on and on about it, and it was chilly out. And there was not a single person in the audience who didn’t already know quite well that people were in prison and land was being stolen. There’s a time and a place to be reminded of these things, but I wish they would just let folks enjoy a concert once in a while.

One of the speakers actually was quite enjoyable. He came on stage, an imposing figure with a long white beard, flowing black robes, a cylindrical black hat with a train of black cloth flowing from the back and sides, an enormous golden amulet necklace, and a long black staff with a silver orb on top.

I heard a Belgian guy ask an American girl next to me, “What is he, a priest?”

The American girl whispered, “I don’t know, maybe he’s Greek Orthodox?”

I leaned over and whispered, “Actually, I think he’s a wizard.”

He was a Greek Orthodox priest, and he spoke in ringing formal Arabic to the audience of mostly Muslim Palestinians about steadfastness and human dignity and freedom for this little nation, and the crowd loved him.

He really did look like he should be teaching Dark Arts at Hogwarts, though. Talk about pageantry. The Holy Land is kind of adorable that way. All the real power has moved to Rome and Riyadh and New York. But this dusty little strip of land still has style.

Combatants for Partying

The night after that there was a party on my Dutch friend’s roof with several of her friends from Combatants for Peace, “a group of Israeli and Palestinian individuals who were actively involved in the cycle of violence in our area. The Israelis served as combat soldiers in the Israel Defense Forces and the Palestinians were involved in acts of violence in the name of Palestinian liberation. We all used weapons against one another, and looked at each other only through weapon sights; however today we cooperate and commit ourselves to” a non-violent resolution to the conflict.

Three Israelis braved the checkpoints to come to the party (and three others would have come if their car hadn’t broken down in Tel Aviv) along with a handful of Palestinian ex-militants/freedom fighters, other Palestinians, and some internationals, including a Jewish guy from Canada who’s working as a journalist for the Palestine Monitor. One of the Palestinians brought an enormous fruit salad, and another cooked kofta bandoora (spiced minced lamb baked with succulently tender, delicately-spiced potatoes and tomatoes), and we feasted on that and wine and beer in the cool night air.

It was humbling to speak with Israelis who had previously been in the very same role as the people who currently make life so pointlessly difficult for so many good people here. People who in reality are caught up in the terrible game almost as helplessly as the rest of us.

These Israelis had been big enough to look past their brainwashing and humbly change their lifestyles and accept the consequences of realizing and accepting their own truths. Even enough to come to scary scary Ramallah after dark for a kofta party on a rooftop without a trace of fear. (No one who’s ever been a guest in Palestine will be surprised that the Palestinian ex-militants stressed to them over and over that “You are most welcome here any time.”)

One of the young Israeli women, now a photographer, said that the first thing that caused her to reexamine her belief that Arabs were nothing but crazed enemies was when she was manning a checkpoint in the West Bank and a random Palestinian woman about the same age as her mother brought her a gift of home-baked bread.

The story reminded me of the practice of ‘impressment,’ which allowed occupying Roman soldiers to conscript any Jewish person in the Judean provinces to carry his equipment for one Roman mile. Jesus said in the Sermon on the Mount, “If a soldier forces you to carry his pack one mile, carry it two miles” (Matthew 5:41). This is an (admittedly back-breaking) way of turning a situation of slavery into a situation of free will and service to a higher law.

And there’s an undeniable power in this. Christianity didn’t spread to 1/3 of the world’s population by the sword (and the whole burning-alleged-heretics-alive thing) alone.

One of the Palestinian ex-militants, who was one of the founders of Combatants for Peace, said his epiphany came when he was hiking in Wadi Qelt, a valley located between Jericho and Jerusalem, with some Palestinian friends when the weather suddenly turned bad. As they were trying to figure out what to do, they came across some Israeli settlers who were also hiking the valley, and they all worked together to get safely back to civilization.

“Now I could see,” he said, “they aren’t just crazy people trying to take my land. They are also human beings.”

(Dire Straits just came on the RamFM radio station here at Pronto. Life is good. I just wish I could afford more wine.)

After that there was another party at the Grand Park Hotel, which I normally avoid because it’s generally full of people who are too stylish and self-conscious for my taste. But “everybody” was supposed to be there, including a couple of Palestinian hip hop artists, and someone offered me a ride to it, and I was already dressed up, so I went.

The music choice was unfortunate (mostly loud and monotonous Israeli-style techno) until about 3am, when the hip hop guys did some songs, then the DJs switched to infectiously danceable Arabic pop music. And it was nice to see “everybody.”

At one point, though, I was talking to someone and suddenly felt a sharp pain in my throat, as if I’d inhaled a bit of burning cigarette ash. Soon the pain spread and I realized what it was — tear gas.

The guests retreated to the fresh air outside, and the security guys worked on sealing the exits, airing out the dance floor and bar, and seeing if they could find any clues as to who the culprit had been. (Probably just some idiot who couldn’t score with some girl he liked.)

In any case, after half an hour the party was back on. Almost everyone had inhaled tear gas before, so nobody panicked too bad. People were kinda pissed, but on the scale of things, this was a non-event.

Just as I was sitting here writing this in Pronto, two Palestinian friends showed up, and one of them was talking about how it was always the public that initiated change and the leadership that co-opted and capitalized on it, and in the process often perverted it toward their own personal ends. Like how Arafat had nothing to do with the First Intifada, but he ended it by signing the Oslo Accords and then allowed Israel to double the settlements in the West Bank between 1993 and 2000.

He spoke of one particular Palestinian politician who had signed on to a peace deal with Israel that was not a good deal and did not pave the way for a just peace. But he did go quickly from being nearly penniless to driving a late-model BMW. And of course there’s the infamous case of a certain high-level Palestinian politician making money by investing in a company that had secured a contract to build the Wall.

My friend said, “It’s always the same here. The people make history; The leaders make investments.”

Yesterday I and a friend enjoyed a bacon-and-eggs brunch with stone-baked rosemary Italian bread and a fresh apple-orange-carrot juice cocktail, then we visited a Swedish girl whose cat had just had kittens. I rounded out the day with a three-hour Turkish bath — steam sauna, small cold bathing pool, hot stone platform to lay out on, full-body exfoliation, stone basins of warm water and olive oil soap to wash with, and top-notch massage. A perfect Sunday.

.

Deleted passages follow the underlined portions on the pages indicated.

CHAPTER 6: BOMBINGS, WEDDINGS, AND A KIDNAPPING

Disappeared

(p. 129) Shadi is silent for a moment. “Please call me if you hear anything.”

“I will. Same to you, OK?”

“Of course.” I hang up and think, Qais must have told Shadi he was coming to visit me, even though it was supposed to be a secret. I feel a slight pang of betrayal, but it’s quickly replaced by the realization that it was a very sensible thing to do in a time and place where he knows he can disappear at any moment without warning.

(p. 131) If you want to live in Palestine and not be a complete greenhorn ajnabiya, you’ve got to put a little starch in your spine.

On the one hand, I dread and fight against losing this sensitivity. If I begin to accept things no one should ever accept, I’ll have lost a part of my humanity. But if I weep for every kid killed in Gaza, if I waste a day with my gut aching hollow and my back bent in dread and fatigue every time a friend disappears, I’ll never stand up.

But if we don’t put ourselves in others’ shoes now and then, we risk losing sight of the silent helpless horror that lies just below the surface of what we think we know. We can’t ignore it just because it is silent, snuffed out and shut up. It is there, manifestly, and it will come for all of us if we don’t put out the fires somehow.

Shoot ’em Up

(p. 139) At the end of the week, feeling exhausted, I went with Yasmine to

a place called Almonds, a cozy dance club near Sangria’s. It felt amazing

to forget everything for a while and just dance. I’d never heard

anything as infectiously, shoulder-shakingly danceable as Arabic pop

music. People kept buying my drinks (including an ex of Yasmine’s,

though I wasn’t sober enough at the time to notice her ire), and I chatted

with cute Palestinians and fascinating foreigners on the balcony

outside with its little potted palm trees.

Two days later a Belgian girl got married to a Palestinian man in Ramallah, and Osama invited me to their wedding. I borrowed a slinky amethyst evening gown and white satin shoes from Muzna and got my hair cut and styled. The wedding was in a swanky banquet hall at the Casablanca Hotel near the Clock Circle. The crowd was young and sleek, drinking beer and Johnny Walker at their tables and dancing to Arabic and Western pop music at an ear-splitting volume. Afterwards Osama and I had sangria at Sangria’s with some of his Communist friends, and we talked and joked and laughed. It was the perfect cap to a gorgeous weekend.

A few days later the Israeli army invaded Jenin with thirty tanks backed up by aircraft. With my heart in my throat I called Qais to make sure he was OK.

“I’m fine,” he said in a soothing tone. “Don’t worry. It’s normal.”

I rested my forehead wearily on my arm. Sweetie, it’s not normal.

Zeitoun

(p. 144) Every few minutes Thaher would yell from whatever tree he was in, “Heyyyy, ya ammmmmmi!” He was greeting a favorite uncle, Abu Dia, and when breakfast was called I met the great man. He told story after story with a stone-straight face and a subtle, sincere voice that had everybody in tears from laughter, including myself even though I could barely understand a word. Nael turned to me, his eyes moist with mirth, and asked, “Did you ever watch the Cosby Show?”

“Sure.”

“I think Abu Dia would be bigger than Cosby. He says all of that with no preparation.”

(p. 147) The kids were adorable and funny and full of energy, and they played any game they could think of while we picked olives. Armored vehicles patrolled the access roads that ran along the Fence, and each time they came into view the kids would excitedly yell, “Hummar! Hummar!”

When things became too quiet we’d call out each other’s names: “Ya Shadi!” and wait for acknowledgment: “Na’am?” and ask, “Keef al saha?” (How’s the health?), “Shu akhbarak?” (What’s new?), or “Keef halak?” (How are you?) Qais told me to answer, “Ahsan minak.” (Better than you.)

When that got old, I started listing in Arabic all the things I was better than, including carrots, Yasser Arafat, and the King Hussein Bridge. When I said I was better than khara (excrement), Qais laughed and asked, “W’Allah?”

“Taqriban,” I answered cheerfully (almost), and everyone laughed.

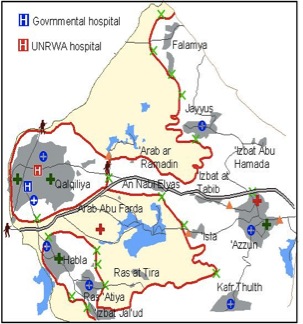

A piece of Qais’s family land where they now have only seven trees. They used to have twenty here, before the Wall.

You can see how close the Wall comes to the village, even though the Green Line is four kilometers away

Days of Penitence

Iman al Hams, the little girl killed by the Israeli army sniper on her way to school on October 13, 2004

A t-shirt made by an Israeli army brigade mocking the deadly violence that killed hundreds of civilians in Gaza in 2008-2009.

(p. 155) “No. These may be my last days. In a way, I hope so.” I couldn’t tell if he was joking or not. He sighed exhaustedly. “Ya skuchaiu po-Allah.” (I miss God.)

Suddenly I was overwhelmed by a flash of anger. I wanted to shout, “Fine, just give up and sleep in for all of eternity! How can you even say that to me?”

But who could watch so many proud young women and dignified old men humiliated at checkpoints? Who could watch the obscenity of helpless, impoverished, dispossessed people being bombed in Gaza like fish in a barrel? How long could and should someone stand it? A diminished life was better than no life. There was always a secret space no oppression could ever touch. But how could a valiant, or a sensitive soul bear it?

CHAPTER 7: ARAFAT’S FUNERAL

The beginning of this chapter should have been a section called “Grapes of Aboud” that ended up getting cut. Read it here.

Ramallah Ramadan

(p. 158) But I loved the star- and crescent-shaped lights glowing in windows and public squares and the special greetings of the season.

One evening two friends from Jayyous named Ali and Fadi were visiting Ramallah, and they invited me to join them for Iftar at a restaurant called Tel al Qamar (Moon Hill) on the top floor of a building on Main Street. Ali was a dapper high school counselor with a mellow baritone voice and an impeccably-groomed goatee. Fadi was a skinny young man with big brown eyes who liked to make puns in English. He had just come back from the Muqataa, where he’d delivered homemade food to his brother who worked as a guard there.

I asked Fadi, “How’s old Arafat doing anyway?”

“He is fine,” Fadi said. “You know any good Arafat jokes?”

I told him I didn’t know any Arafat jokes, and his eyes lit up at the prospect of a new audience. He told me a few that made fun of how Arafat’s lips trembled involuntarily:

There was an earthquake in Palestine. Why? Arafat decided to kiss the ground.

A man asked Arafat, ‘Why do your lips always move like that?’ Arafat answered indignantly, ‘I’m talking on the telephone!’ An aide beside him started moving his lips, too. The man asked, ‘What are you doing?’ The aide answered, ‘I’m receiving a fax.’

Someone asked Arafat, ‘Why do your lips move like that?’ Arafat said, ‘Sorry, my mouth is in Area C.’

Others made fun of Arafat’s powerlessness:

At a press conference after Israel bombed the Muqataa, Arafat held up two fingers. A reporter said, ‘Are you crazy? Why are you making a V for Victory sign?!’ Arafat said, ‘No, no, I’m saying stop bombing, I only have two rooms left!’

Fadi was interrupted mid-joke by the call to prayer. We got in line for appetizers: dates, almond juice, and vegetable soup infused with cardamom. Several men lit cigarettes immediately, but neither Ali nor Fadi did. I remarked on this to Ali.

He said almost cheerfully, “Sometimes in prison, the Israelis will take away a man’s cigarettes to pressure him. I don’t want anyone to have this kind of power over me.”

I looked at him in amazement. “How do you say this kind of thing with a smile on your face?”

He shrugged. “Yes, we smile. But you have to understand. Sometimes we are smiling with our mouths only.”

A musician played the lute and sang beautifully, and a view of the waxing crescent moon was framed perfectly in a window. Eating good food felt marvelous after the long hungry day. I could practically feel the nutrients percolating giddily into every cell.

On the first of November, I was finally able to move into the apartment provided by my employer. It had a huge living room with comfy blue couches, satellite TV, a sunroom, a bright, clean kitchen, and three bedrooms. The windows overlooked the Plaza Mall shopping center, which has a Western-style supermarket, hair salon, Italian restaurant, and dry cleaners on the lower level. Upstairs is a coffee house popular with teenagers, a fast-food joint called McChain Burger, a toy store, and an astronomically expensive United Colors of Benetton.

Palm trees lined the front of the mall, and a mosque with a tall white minaret blasted the call to prayer five times a day from behind it. Empty villas sat in the hills above, the abodes of diaspora Palestinians who had left due to the violence or been denied IDs or visas and thus had been bureaucratically expelled. I frequently heard gunfire from the settlements nearby, but it was usually far away and soon became part of the normal background noise.

On the day I moved in, three Israelis were killed and more than thirty wounded in a suicide bombing at the Carmel Market in Tel Aviv. The Nablus branch of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) claimed responsibility. The bomber was only sixteen years old. The PA condemned the bombing, and a Nablus spokesman for the Al Aqsa Martyrs Brigades said the bombing was an “embarrassment to the Palestinians seeking to reorganize their own internal affairs” (even though the Al Aqsa Brigades had committed the previous bombing).

The news didn’t make much of an impact in Ramallah. Three more people killed far away by a group none of us belonged to barely registered. It was just more of the same—carnage on top of carnage, crimes on top of crimes, and no end in sight.

Osama called a few nights later and invited me to a restaurant called Ziryab (‘blackbird’). It was the nickname of a famed Iraqi poet, musician, fashion designer, geographer, botanist, and astronomer in the 9th century Umayyad court of Córdoba in Islamic Spain. He was reportedly a former African slave, and his nickname was due to his dark complexion, eloquence, and melodious voice.

(p. 159) It seemed a strangely irreverent thing to do given that only a few days earlier, Arafat had been flown to a hospital in Paris suffering from a mysterious illness.

I mentioned this to Osama as we were walking home. He said worriedly, “Yes. If Arafat dies, there’s a chance Israel will invade Ramallah with tanks and helicopters again.”

A thrill of excitement passed through me, followed closely by dread. A full-scale invasion in Ramallah… Tanks! In the streets! Jets and helicopters circling overhead. Blood, bodies, and broken glass. It seemed impossible that it could happen here. But it had already happened here, in 2002.

Rest in Peace, Abu Ammar

(p. 162) A brief controversy arose over Arafat’s final resting place. He wanted to be buried in East Jerusalem near the Al Aqsa Mosque, which everyone knew the Israeli government would never allow. In order to avoid an awkward confrontation, Palestinian leaders suggested he be buried in a stone tomb in the Muqataa in Ramallah, which could be disinterred and reburied if and when East Jerusalem came under Palestinian sovereignty.

Omar’s Story

(p. 170) Soon it was time for me to go. Dan had agreed to pick me up and take me back to Jayyous in a borrowed van. I shook Omar’s hand and held it for a while as I met his pale blue eyes with mine. There was nothing to say. We were fundamentally no different from each other. Yet he knew as well as I did that I would never have to come to terms with a misfortune anywhere near as incomprehensible as his. Something horrific might happen to me, but I probably wouldn’t be shot for no reason, and I certainly wouldn’t be transferred to a foreign country and held captive by people whose indifference was somehow worse, more degrading, than cruelty.

I left the hospital in a daze. After walking a few steps in the fresh air, I ducked behind a column and sank to the ground and wept. On the weight of my tears was not just Omar but all the people like him whose stories would never be told and for whom help would never come.